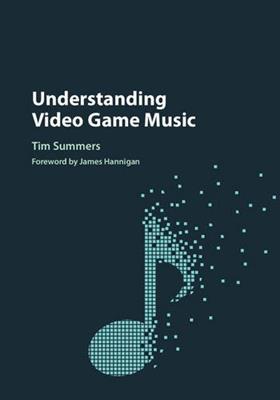

Tim Summers Interview: Understanding Video Game Music

In his recent monograph Understanding Video Game Music, Tim Summers (Royal Holloway, University of London) takes the study of game music, or ludomusicology, and conducts a thoughtful academic analysis of the field. The book features an introduction by Command & Conquer‘s James Hannigan and explores methods for understanding video game music on its own terms – not as a offshoot genre of music, but as an entire branch in its own right.

In this interview, Tim Summers speaks about his approach to writing the book, and how he chose which topics to address in a field that has been largely unexplored. He speaks about a vast range of game scores from Halo to Zelda to Monkey Island 2, and examines their unique and interrelated qualities.

Interviewer’s note: Those interested in purchasing the book may find it here at the Cambridge University Press website; enter the code “Summers2016” at checkout to receive a 20% discount. Understanding Video Game Music is available now in Europe, and will be available in the U.S. at the end of October.

While the book is written from an academic perspective, the writing is accessible to any reader interested in learning more about the background and common qualities of game music.

Interview Credits

Interview Subject: Tim Summers

Interviewer: Emily McMillan

Editor: Emily McMillan

Coordination: Emily McMillan, Chris Greening

Interview Content

Emily: How long has Understanding Video Game Music been in the works?

Tim Summers: It’s based off the research I did for my PhD at Bristol University from 2009-2012. So a lot of the core ideas were created during that time. But then, after I finished, I used that information to write it into this new book. So it’s been going since then. The idea for it predates even that. Ever since I went to university, I’d always been playing games, but I hadn’t really thought about it in an academic way and taking the music seriously until I got to university, and I started to apply the same kind of thinking that I would to traditional music, classical music, film music – and I thought, why not video games?

Emily: I loved the chapter about the influences of Hollywood culture on game music. Games in the 80s and 90s were introducing music in new ways, using this concept of being interactive and player-responsive. And then something like Zelda comes along, with an especially Hollywood sound that is very reminiscent, as you say, of older composers like Korngold. How intentional do you think that musical influence was?

Tim Summers: The project that I’m writing right now is a book specifically on a Zelda game – specifically on Ocarina of Time, so I’m going to reference the game a whole lot more then. Do I think it was a conscious, deliberate decision? “Let’s go and reference Korngold?” Not necessarily. I think it’s more that these musical signifiers are a part of a more general musical lexicon. Unlike John Williams in Star Wars referencing Korngold in a more deliberate way, I think this is more a part of those received musical signs about what people perceive as heroic.

Our idea of what that ‘heroic’ sounds like, though, is a part of what’s constructed from those Korngold scores. I said in the book that my life runs contrary to that chronology – so I understand Robin Hood because it sounds like Zelda, rather than the other way around. So I don’t think it as a conscious decision, but I think it’s part of a more general concept of heroism in music.

Emily: Regarding this previous knowledge of music, you talk about the concept of intertextuality, that players depend on their knowledge of music from other games in order to play the next game. How significant do you think that prior knowledge is in picking up a game?

Tim Summers: I think it’s something that’s taught, musically, as we play games. As we play different kinds of games, we learn what those musical signifiers sound like. By playing games, we learn what, for example, the characteristics of battle music in a JRPG is. We become fluent in those musical languages as we play the game. As you play these games, you learn what these sounds are – as you go into battle, it’s more up-tempo, increase the jagged figures, increase the texture, polyphony, change the key. By doing this, we learn how to interpret those signs.

You’re also onto another important thing, which is, what do those sounds actually involve more specifically? We learn generally, but what are the specific musical characteristics of, say, boss music? That’s something I’m still trying to pin down.

Emily: You had that one story about a friend who was playing Resident Evil as one of his first games, and was learning how to figure out whether the area was clear of enemies by whether the battle music was still going or not.

Tim Summers: Yes, exactly. Yes. And that was somebody who is a very dear friend, but he wouldn’t call himself a musician. He hasn’t had formal musical training. He does play a mean tambourine! But that’s about it. So yes, he learned what that musical sign represented by playing, and I think it’s a neat illustration of how it doesn’t necessarily happen only to people who are experienced in music or gaming, but it’s something that happens to everyone, no matter their background.

Emily: I like that you mentioned the difference between Eastern and Western music – I grew up on JRPGs, but just finished a playthrough of Bioshock, which is hugely dissonant and eerie and unsettling when you go into a battle, and is very different from that sort of up-tempo, almost pop-influenced JRPG battle theme.

Tim Summers: Absolutely. I did a bit of research a while ago that isn’t in the book that centers on the difference between Japanese and Western RPGs, and about how these different traditions work. The idea is that Western RPGS kind of say, okay, here’s your world, make your adventure, within certain limits. It’s musically focused on actions and places (battle themes, location themes, etc.). The point is the player freedom, as opposed to JRPGs, where you’re following a specific set of characters and a specific storyline, and as a result you have this very thematic, melodic musical style. These focus on character themes with very obvious musical communication about the roles you play. And that ends up being material that people love and listen to repeatedly.

This brings us back to this paradox of repetition in game music. Conventional logic goes that we don’t like too much repetition. And yes, game music can end up being annoying. But there’s also a joy in repetition – that actually, having these themes going round and round again in a medium that is inherently repetitious anyway –there’s something interesting there.

If we take the position that too much repetition is bad, then why are these video game melodies so obvious and prominent – and why do we love them so much?

Emily: You also mentioned in that chapter that westerners tend to have a certain expectation when they listen to an album. Each track should follow a certain procedure – it will have a beginning, and ending, a development section, and so on. And for a game album, this kind of goes against what a typical piece of game music might sound like.

Tim Summers: Yes, yes. And this applies also to the idea that what we hear in a game is going to be different to what we hear in the album. There’s a different kind of listening involved.

Emily: Do you have any philosophy for how a game album should be arranged?

Tim Summers: Good question! I think it depends on the agenda. Different audiences want different things. You have those who want to hear every note in the game – the album is an archive in this case. You want the album to have all the material in it, and that’s one kind of approach.

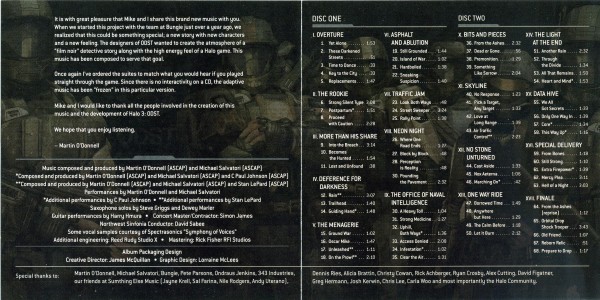

There’s also a different kind of approach, which Marty O’Donnell talks about in his liner notes to the Halo album. He wants to represent the players’ journey through the game in his tracks. I’m paraphrasing here, but he says something to the effect of, you might hear something in the soundtrack that you didn’t hear in the game, and you might hear something in the game that you won’t hear on the album, and that’s because you’re playing the game in a different way.

So yeah, I think there are different expectations. So you also then go back to the question of, do you do an arrangement or a remastering? I love those Zelda 25th Anniversary recordings – do we want to see music we love rendered somehow, in high quality or with beautiful sounds? Maybe when we listen to music outside the game, the music has lost something outside of the game. Or maybe it’s liberated.

Emily: Well, in that same chapter, you have this quote from Marty about how you might play the game and hear the music in a way he never anticipated. Do you think that can be disconcerting to the composer?

Tim Summers: I think it can be. There are two ways that could happen. One is in terms of glitches, or where you decide to manipulate or change the music. You substitute your own music into the game, which most composers wouldn’t be too keen on.

But for most composers, even generally, you have to allow the audience to interpret the music in their own way. Music doesn’t “mean” in the same way that language does. Part of the beauty of music is in its ambiguity. That’s why we keep listening to it, creating it, the joy is in that ambiguity.

I think games are good at that, because they put music in this context that is meaningful because we interact with it. Often when you’re listening to music repeatedly in different situations, it allows you to create different meanings for those same pieces. Both music written for the game, and even for outside the game. I listen to The Ink Spots differently after Fallout. It enriches the game and the game enriches the music.

Emily: I was actually wondering what your thoughts were on that – the idea that the game itself gives you a way to listen to the radio and basically blot out any score Inon Zur wrote.

Tim Summers: Yeah, I think it comes back to the idea of player agency, which is very different from a JRPG. I’m given the opportunity to create my own meanings to the music and the game, unlike the more constrained (not necessarily in a bad way) game like a JRPG. What does it mean for the soundtrack? It opens up more possibilities.

I first encountered the Ink Spots when my grandfather bought a CD of them. I remember buying it and putting it on – he’d just bought a CD player, and this was one of the CDs he had bought. That nostalgic value is important to the game and for me as well – it gives me a personal resonance in the game. The preexisting music can do that. At the same time, we also get that original music that draws on a different experience in a different way.

Giving the player agency of the music allows them to choose the music they like best – not in the sense of the music itself, that I like this tune, but in the sense of how it pairs with and accompanies the game.

Emily: You also say that music doesn’t just accompany a world or a playthrough, but that it is a part of the world and the playthrough experience. Does having preexisting music like that in any way decrease the value of the world of the game?

Tim Summers: I’d argue the opposite, actually. By having those pieces from the real world put into the game music, it provides what I call an audio portal – a sonic link – into the game world. It creates a connection between the two worlds. Often, in terms of a realism. In a game that wants to be semi-realistic, you have radio shows, real-world tunes, and so on. So it helps to populate that virtual world with real world things. But I think if your agenda is to create a world that is as far apart and mystic as you can make it, then that choice wouldn’t work.

Emily: So you talk about game music for historical games as well, which is very interesting, where composers are creating soundtracks based on music that may have existed at one point.

Tim Summers: Historical games have a very tricky challenge. Composers have to try and build this idea of a historical world, but while (in many cases) you can use music that may have existed at that time, does that actually build the world in the best way for the player?

So for example, Age of Empires III, which I talk about a little bit. There’s a load of music you could use that are from those times. But for many players, using Hollywood music that’s associated with historical worlds, is actually more familiar and connotes those historical worlds more effectively. Plus, it gives it that fictional gloss as well. So you have to walk that line.

It’s interesting that you can put a game like Age of Empires, which tries to be more accurate and historical, next to a game like Civilization, which does use real-world music, but that game isn’t so keen on being absolutely historical. It embraces anachronisms quite a lot. There’s some weird thing there – if you’re obviously uninterested in being historically accurate, you can use that sort of real-world music as a way of showing your historical credentials. But in Age of Empires, when you’re creating a fictional history, you sort of have to make a musical investment in the Hollywood scores to help connote that.

Emily: You described those games and/or their music as being fictitious – is the reason for that how the players can go through those games?

Tim Summers: Yeah, I’ve called them “fiction” to denote that level of reality, to say that even in a game that attempts to be historically accurate. Even the early Call of Duty games are fictional because of that world they create. I don’t mean it as a commentary on their fidelity to history as such. If you take something like a really good fictional book that was set in Tudor times, even if it was really accurate and the author had done all their research, it would still be fictional because of the story the author is creating. In the games, the actual discourses created through play create a fictitious environment.

Emily: You talk about the start-up music of consoles – hearing that orchestra tuning for the PS3, and so on. Why did you spend that time talking about that?

Tim Summers: That’s me being…deliberate punk-y. I don’t know. [laughs] Trying to be provocative! There is a value thing that goes in any academic study. It’s unavoidable to a certain extent. We write about the games we want to write about – what is the most interesting. With video game music studies, there is a tendency to focus on musical examples that show off the music and say, “Look, this music is as good as…”, rather than saying it’s good in its own right. It’s as good as film music, it’s just like classical music. That’s a problem, because it’s saying, this is good because it’s a bit like other stuff that you’ve recognized as good, instead of, this is good in its own right.

So part of what I wanted to do was – it was twofold. One was to say, look at how the whole experience is musical, from the moment you turn on the console. The music goes all the way through the musical experience.

Second, I wanted to say, let’s not ignore these sort of – “low value” pieces of music. They are important. Particularly because you hear them each time you turn on the console – they might be small, just a few notes – but you hear them over and over again, each time you turn the thing on. They can be remarkably evocative.

The example I cite is Frank Ocean’s Channel Orange album, where he uses the Playstation startup cue. When I hear that, I can remember sitting on the floor of my living room, turning on the Playstation I had borrowed from the Local Youth Club over the weekend. I remember it viscerally.

So I’m being deliberately provocative, yes, but I also want to say that we shouldn’t ignore these sounds, because they are part of the experience. Even if it’s tiny, it can still be meaningful.

Emily: That’s incredibly interesting. I was kind of a “late gamer,” and when I hear the music, I tend to think of the game I played most on that particular console. The PS3 music always makes me think of the game I clocked the most hours in while on that console – I think of that over the console itself.

Tim Summers: Yeah, it’s interesting what you say. I emphasize this a lot – we like to focus on the big cues in the game, the big tunes, the famous levels, “One Winged Angel.” But, like you said, there are small sounds that are part of the whole experience. The connectedness in those small sounds – and the whole thing – is so important.

Emily: On the subject of comparing music to Hollywood or classical scores, you included a quote from James Hannigan (who also did the intro) that that game music shouldn’t be like anything else – it should be compared to only itself. Is the How did he come on board and why did he say that?

Tim Summers: Absolutely. You’re right when you say there is this emphasis that says, “Oh it’s good because it’s nearly Hollywood,” which is a false standard because they are different media. Yes, they share similarities, not least in the cutscenes, but the experience is different. This is why films based on video games aren’t always terribly successful, because they have different priorities, and there is something about that interactivity about games that’s different, which I definitely wanted to highlight in the book.

Coming across James’ writings and his music, which is so distinct, it’s not just your background music – it’s more than that. I said this in the book – that music in games is often more aesthetically impactful than it is in the cinema, and saying it could be like the cinema is a false model.

I had interviewed James when he came to speak at a conference I organized with Michiel Kamp, Mark Sweeney and Stephen Baysted at Chichester University on game music. It was part of our on-going annual Ludomusicology conferences. James came to speak along with Richard Jacques. James articulated this idea of game music embracing its difference in his talk, which is why I asked him to write something for the book. He very kindly agreed to write the foreword for it. But it comes back to emphasizing the importance of music in video games- it’s a part of how we play the game. So I’m very fortunate to have James take time out of his busy schedule to write it – it was very flattering.

Emily: I thought that what he said, as well as the extra quotes you included in the part, complemented your text very well, because you’re saying that game music is an integral part of the game’s world, and he’s saying that game music is an integral genre of music.

Tim Summers: Yes, thank you – I think we were very much on the same wavelengths during the book.

Emily: The last thing I wanted to look at was your chapter which focused on Final Fantasy VII, where you write about the prevalence of area themes as something that makes games very different from any other kind of genre. You can have thematic elements, and themes to represent people, but the idea of having themes to represent places is standard for games, but unique to most other musical mediums. What brought that to your attention?

Tim Summers: It’s in other media as well – in Lord of the Rings, for example, you have distinct sounds and themes for different areas, but it’s so prevalent in games. I think it came back to this idea of music being a part of this world.

There’s a theorist I draw upon named Ben Winters, who writes on film music. There’s a big thing on film music criticism – if you go into a course of film music criticism, you learn about diegetic music and non-diegetic music. You have diegetic music, which the characters in your film can hear, and you know that the music is a part of their world, and you have non-diegetic music – that’s like in Star Wars, we don’t think that the orchestra is in the same world as the characters. It’s on the outside.

Winters says, if we talk about non-diegetic music as being apart, that does the world a disservice, because it is very much a part of that world – it’s part of how the characters are made, how the worlds are built. I was thinking about that in terms of games, where the music contributes to the worldbuilding. Especially in games like Final Fantasy VII, a brilliant game – but you look at it, and it’s kind of blurry, sometimes it’s very small, sometimes you go off the screen and you don’t know if you’re in the same area or not. But the music continues, and it helps you know where you are, and it helps build the geography for you. So the music is part of how the world is constructed, part of the geography – perhaps even more so than in films. So it’s not something that stands outside the world.

Emily: I was kind of laughing when you mentioned in that chapter the parts in JRPGs where you’re grinding at the end of the game, and I’ve always found that moment funny when you’re running from area to area and you’re hearing five-second intros to each theme that end when you hop back onto your airship – it’s like a little montage of the areas.

Tim Summers: Yeah, and you’ve brought something else to mind – because you’re also highlighting the musical structure of your experience of the game. It’s like a recapitulation of the symphony. Maybe it’s also part of structuring the whole gaming experience. You have your sense of recapitulation – the other example is in Monkey Island 2, when you go to the areas and come back to the main area, it sort of makes a natural rondo form.

Emily: Towards the beginning of your book, you have an apology for being very broad – you cover a lot of topics in your book, which is a bit over 200 pages. If you had the opportunity to delve more into a specific field, what would you have liked to expand on?

Tim Summers: I think that there are two particular directions I’d like to take my research into from here. One is a little bit more on film music versus game music; the similarities and differences. Particularly in a multimedia world, when you have franchises that operate over these film, TV, video games – it’s not as simple as just having these things in isolation.

The second dimension is research on music and sound in virtual reality, as we’re finding things like the Playstation VR, the Oculus Rift. As these things are becoming more popular. I’m very interested in examining how music and sound work in that environment. Simply something like VR asks us to deal with particular questions – when you watch a film, and perhaps to a lesser extent when you watch someone play a video game – you’re not having to deal with where that sound is coming from. Whereas in virtual reality, questions like that become very important. When you’re in a virtual reality, you have to rethink where the sound is coming from. So that’s something I’m very interested in delving into as well.

Emily: You also mentioned earlier that you’re looking at your next book – can you tell us about that? It’s about Ocarina of Time?

Tim Summers: Yes, that’s the plan! Still fleshing out the details – that’s next year’s job! The idea with this next project is to be an incredibly detailed in-depth exploration of a modern game. I chose Ocarina of Time for many reasons – one is that we can’t deny that personal aspect of writing about music, and that game is personal to me. But that game provides a good case study because it interacts with all of these different ideas, particularly with performance in the game, playing within the game, the way the world is built around game music. It also represents a turning point in game music. That’s partially why I’m drawn to the music. And the fandom that surrounds it – it’s got such a long afterlife, and it sits very well among the other games of the Zelda series.

Emily: That sounds like your chapter that features Loom, where the player interacts directly with the music as well.

Tim Summers: Oh, I love Loom, I never shut up about Loom. [laughs] I can always talk about Loom and Monkey Island. If it’s a Lucasarts or Sierra point-and-click game, you can guarantee it will appear at some point in something I’ve written. That and The Dig, which I’m a big advocate for – I encourage anybody to go and have a listen to some of the music from The Dig. It all comes back to this overarching idea of music and play – and making the games fun, and enriching our experience as players.

Emily: Is there anything else you would like to say about your book Understanding Video Game Music?

Tim Summers: A book like this is also shaped by the people that I work with and with whom I discuss ideas. I’d like to give a shout-out to my good friends and academic colleagues at the Ludomusicology group, Michiel Kamp, Mark Sweeney and Melanie Fritsch, as well as the work of academics Karen Collins, Will Cheng and Will Gibbons, all of whom inspire me.

One thing I’d like to put out there is that I don’t necessarily want everybody to read it and agree with me. I think more than anything else, my ambition for the book is that it starts conversations. I want people to read it and maybe entirely disagree with me – but if I can continue this conversation, and be a part of the energy to take video game music seriously and have fun with it at the same time, I would be very very happy indeed.

Once again, those interested in purchasing the book may find it here at the Cambridge University Press website; enter the code “Summers2016” at checkout to receive a 20% discount. Understanding Video Game Music is available now in Europe, and will be available in the U.S. at the end of October.

Posted on October 25, 2016 by Emily McMillan. Last modified on October 25, 2016.

Great interview Emily and looking forward to reading Tim’s book! His earlier article on Wagner’s influence on game music (‘From Parsifal to PlayStation’, I think) was very insightful, so I hope the book will continue in that vein. Most published literature on game music seems to be either in the form of handbooks on how to write game music, or when aesthetic concerns are considered, the focus tends to be on game music’s interactive nature. That’s a very valid and necessary approach, but it’s good to also see there’s some analysis of the stylistic features of game music (such as the way games might score period subject matter, as Tim discusses). I find the latter approach most helpful when trying to review game music in its album format, ideally in a historical context.