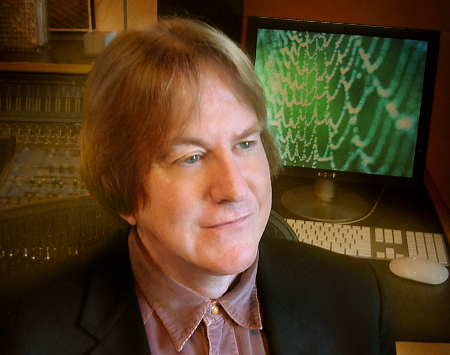

Greg Edmonson Interview: Is Film or Game Scoring More Satisfying?

Greg Edmonson broke into the industry scoring several acclaimed television shows for American networks: Firefly and King of the Hill. However, he is best known for underscoring Nathan Drake’s worldly adventures on the Uncharted series.

In this interview, Edmonson reflects on his work on the Uncharted series and discusses some of the highlights of the newly released Uncharted 3: Drake’s Deception. The scoring veteran also gives his perspectives on game scoring and how it is becoming the most creatively satisfying than working on television and game.

Interview Credits

Interview Subject: Greg Edmonson

Interviewer: Matt Diener

Editor: Chris Greening

Coordination: Greg O’Connor-Read

Interview Content

Matt: Greg Edmonson, many thanks for talking to us today. First of all, could you tell us about your early musical experiences? What led you to become a composer for visual media?

Greg Edmonson: It’s really a simple answer. I moved to Los Angeles to play guitar and soon I started working as a studio guitar player. It earned me a living and kept me busy, but early on I got the opportunity to write for Hanna-Barbera. I didn’t work for them for very long because I moved almost immediately to start working for a guy named Mike Post who’s really a big name in television. I realized early on that I really enjoyed writing and I also liked being in a position of control. I’ve drawn this analogy before — if you’re an actor, you have all the fun but you really don’t control the project whereas if you’re the director you have a lot more pressure but ultimately you leave your thumbprint on the project. Since then I’ve never looked back, and I’m completely thrilled with my decision.

Matt: To look at some of your other earlier experiences, you mentioned working with Mike Post who wrote one of my favourite television theme songs on Hill Street Blues which juxtaposed soft, tender piano music with action and crime scene footage. I was maybe too young to appreciate it in the 1980s, but it struck me as an example of what you can do with music. Did working with Mike Post influence your how you played with music in your television and Uncharted game scores?

Greg Edmonson: It did. All of your musical past leads you to where you are today. You’re absolutely right about the fun things you can do with music. If we were to extrapolate on the Hill Street Bluesthing, you could have a horrible battle scene and play it as action music (sings a very upbeat action theme) or you can play it with “Adagio for Strings”, as they did in Platoon. This allows the beauty of the music to point out the horror of what you’re seeing on screen even more. It’s one of the most fun things about putting music to picture: there really are no rules. You can try almost anything, and if it works — and you can sell it to the director — you’re good to go (laughs).

Matt: In the days before Uncharted, you worked on King of the Hill and Firefly. Could you share some of your memories of these experiences? While they’re very different, did any of your experiences on these projects ever influence your approach on Uncharted?

Greg Edmonson: Firefly was a seminal project in terms of approach and I’ll tell you why. Joss Whedon (who I think is a genius) wrote what I thought was literally the best TV show ever. When I looked at the two-hour pilot I thought, ‘I’m going to be working for ten years.’ Little did I know it was going to be more like ten episodes (laughs). He created a show with nine main characters, which is a huge amount for television, and they all had wildly divergent pasts. You could go on forever in terms of story without repeating yourself, and Joss knew that.

His concept for the show was that we were in a post-apocalyptic world where all of the cultures were thrown together and it was at this point in time that I started to mix in ethnic instruments with more traditional types of music. This was because of the story he wrote; if all the cultures were thrown together, there was no reason why you couldn’t have Chinese flutes tossed into western music. This was a bit of a game changer for me and I thank Joss for it because it was his vision, but I followed through with this concept for the Uncharted series which utilizes the same elements

There are many similarities between Firefly and Uncharted which we can talk about later in the interview, but they’re not dissimilar. I’ll give you a couple of examples: Joss always writes these great, strong roles for women. If you look at Firefly, there are five female characters and they were all strong (in different ways) but also flawed, as we all are as human beings. If you look at Uncharted, you see the same thing: we have two female characters who are strong (strong in different ways) and we have a main protagonist who (very much like in Firefly) is strong but also self-deprecating. It’s not all braggadocio. Both Nathan and Mal are similar in that while they might at times do the wrong thing, in the long run they’re going to do the right thing.

Matt: While the show was short-lived, Firefly really resonated with its fans. What features of its music are you most proud of? Do you feel there was room for you to explore the series’ music further or did you feel satisfied with the arch you established?

Greg Edmonson: There was a scheduling problem and basically I had about four days to do the score. So, I had to work at least 16 hours a day, every day. I would get up and come down to my writing station at 2 a.m.in the morning and I would look at those characters and think ‘I am just so lucky to be working on this.’

Still, Firefly had some challenging points but they would have fixed it and the truth is that they were in the process of fixing it. But with a TV show, it gets picked up and you start filming in say, July, and it goes on the air in September. And by the time that it goes on the air and you see what’s working and what people are responding to, you’ve already got six or seven episodes mostly shot. You can make little changes, but you can’t completely redo them because there isn’t the time or money to do that.

So really a show needs to run for about a year before everyone knows what’s working. Well, the geniuses who were working on Firefly — the writing staff was beyond belief — they all saw what was working but they didn’t get a chance to fix it. 15 episodes and it was gone.

Matt: A lot of game music these days is dark and ambient, whereas the Uncharted series tends to be rich and vibrant. What inspired this expressive scoring approach and what do you think it brings to the game experience?

Greg Edmonson: In all honesty, I don’t know what it brings to the gaming experience but I will give you a little bit of a timeline. I’ve only done three game scores in my entire life: Uncharted, Uncharted 2, and Uncharted 3 (laughs). When Naughty Dog called me for Uncharted: Drake’s Fortune, I tried to walk away from the gig — not because I didn’t want it, but because I had never done a game. I told them this, and suggested that they probably wanted someone who had worked on games before. They said, ‘we certainly could have done that, but take a shot at it.’

This gave me the freedom to fail, which was thrilling. At that point in time, PlayStation 3 was a new product and the engine behind the games was not as powerful as it is today, so I was cautioned about writing too many melodies. They said that they would need to be able to loop some cues in case a player stayed in one place for a long period of time, so if the melodies came around again and again it would likely become irritating. So, the first game was more ambient in nature, but this was OK since we were set in a jungle where ambient music works really well.

By the time we got to Uncharted 2, I said ‘let me write music that feels more melodic and if I’m going in the wrong direction, tell me and we will fix it.’ So, I incorporated more melodies in the second game and happily so; I was thrilled with how it turned out.

On Uncharted 3, they encouraged me to keep moving in the melodic direction but they also wanted it to sound like its own, distinct score. This was hard to do because you can only change it so much but thank goodness they encouraged this direction because we found our way, and while this score is cut from the same piece of cloth it is a completely different score from either of the other games.

Matt: My next question is on that, actually. The scores for Uncharted and Uncharted 2 were already top-notch, both musically and technically. Was there any room to build on these scores for Uncharted 3: Drake’s Deception or did you aim to mostly preserve the core sound of the series?

Greg Edmonson: I’m not sure… and I wish I could think of a clever answer! Amy Hennig, who is my go-to person at Naughty Dog which produces the Uncharted games, is like a film director, but she’s also the screenwriter; she’s responsible for writing the dialogue and also the performances, the casting, and the look of the game. Of course, it’s not just her doing everything — it is a team effort — but she’s my go-to person. Then of course there is the Sony music team who are actively involved and responsible for implementing the music into the game. They are involved every step along the way, which is very helpful. It really is a perfect situation for me.

Both Sony and Naughty Dog encouraged me to explore something different so we looked at changing the instrumentation as we go from one place to another. For instance, Uncharted 2 is set in Tibet so we found the giant Tibetan temple horns and the erhu — this weird, ancient Chinese violin which we could use. In Uncharted 3, we were set in the desert so we used desert instrumentation. The problem is that desert instruments don’t have the same lyrical beauty that Chinese instruments do; nevertheless they were perfect for the environment since everything sounded a bit dry and spacious. Every culture seems to have this wonderful way of finding something that sounds exactly right for the place they live, and you kind of have to go with it. This time, we used a little more vocal — we had Azam Ali come in and sing because we wanted to use her vocals to capture the spaciousness of the desert.

We also found a scale, and I don’t mean to get too complex here, but you look for a scale that people from a certain part of the world use, and then you build your chords upon that. So we used a different scale this time, called a Phrygian Scale. When you build your chords on it, you end up with a certain melodic shape that transports you to a different place.

Matt: That certainly has to help with presenting a different ‘feel’ to the music. Even a casual listener, who may not be aware of the complexity behind it, will recognize an unfamiliar or alien sound to the music.

Greg Edmonson: It does, it does! I wasn’t sure if we were going to lose people because we were using a chordal structure or melodies that were not as western in their scope, but my job is really not to do anything other than to serve the game. So if all of a sudden I can transport people to the right place and they can have fun, then that ultimately is all that I care about.

Matt: You had mentioned that elements of Firefly — specifically, the incorporation of ethnic instrumentation to capture the essence of a certain culture had seeped into the Uncharted series. How important are the incorporation of traditional/local instruments? Was this something you came up with on your own?

Greg Edmonson: I think it’s something that I just do. One of the really fun things about ethnic instrumentation is that it’s like seasoning when you’re cooking; it really doesn’t take a lot: start with a western orchestra and just sprinkle in a little bit of flavour every now and then to give it an exotic feel. Now you make someone feel that ‘We’re not in Kansas anymore’ and that’s what film scoring and game scoring is really all about: Nuance.

Matt: With Uncharted 3, “Nate’s Theme” returns and it has gone on to become the defining theme of the franchise. Could you elaborate on your inspirations for this theme? How do you think it represents the main character and the series as a whole?

Greg Edmonson: I have to be honest with you — I don’t remember where it came from (laughs) but I know I wrote it for Uncharted and, for whatever reason, people locked onto it.

When we got to Uncharted 2, I was completely willing to not do it again but Amy said that we should since it had become familiar. So, it showed up in Uncharted 2 and, when we got to scoring Uncharted 3, Amy felt that we should record Nate’s theme again. The first two games were recorded in San Francisco and this game was scored in London, at Abbey Road which was a big thrill for me anyway but recording it in a completely different environment with a completely different band gave it a new feel, and it worked out quite well.

Matt: You said earlier that you originally became involved in the Uncharted series at the request of the developer. Before that, did you have any exposure to video games and their scores? Did you realize they could be a potential medium for momentous scores?

Greg Edmonson: No, not at the very beginning but I do now. I look back and I think ‘I am so lucky to be involved in this industry.’ There are some great guys who write music for video games. There are some magnificent scores done by extremely talented people, but it just wasn’t on my radar at the time.

One thing that you get in video games right now that you don’t get anywhere else — that you couldn’t even get close to in television — is the budgets. They’re really more like film budgets. In other words, you can record with an orchestra though you don’t really get the same amount of time but you still have the musicians. You get to work on these wonderful scoring stages with magnificent players, and they just bring the music to life.

Furthermore, video game scores right now are embracing a part of music that neither films nor television do. Television doesn’t have the budgets and film is in a much more ambient place. Right now film scores aren’t really all about melodies, they’re more about setting a mood in a certain, ambient way. Video games are really the only place where you can write these big melodies and they seem to work fine.

I think, in a certain way, video games are perhaps the most creative arena for writing music for right now. When you do a film or a TV show, they’ve basically already shot and edited it before you ever see it. Then they’ll say, ‘Here’s the scene. You want to start at this point and end at this point’ but all of the visuals are already done. This isn’t the case with video game production. I can’t say for sure what everyone else does; all I can tell you is how Naughty Dog works. They might give you an idea of what a specific level will ultimately look like and ask for music that fits that, but they don’t have anything to show you. And in all honesty, they never will because it comes together so quickly near the end of the project that you can’t wait to see the finished product. So you have to write using your imagination, because there’s no finished picture. Every day is an exciting journey, because every day it changes.

Matt: Is it exciting to be involved in such a new medium?

Greg Edmonson: Video games are a unique and interesting phenomenon, but the thing none of us really know is where it’s all going. Films have been around for a long time and we all know how they are done. There have been good ones and bad ones, but we all know how it’s done. Same thing with television — it’s been around since the early fifties and we all know how it’s done. The budgets aren’t as big, but we all know what to do. Video games are changing so drastically. Even on the three that I’ve done, the game engine has changed so drastically from Uncharted to Uncharted 3 that I’m able to do things now that I couldn’t even conceive of when I was doing the original game.

So video games are changing, and we just don’t know where it’s all going to go. I see them as becoming more emotional. I’ve noticed that what Amy does is exactly what a film director would do: you start with a really good script, you cast it with really good actors, you write a story that really matters, and then you fit gameplay into it. There are some games that start with gameplay and write a story as an excuse to get from gameplay to gameplay, but that’s not what Amy does. She tries to make characters that you care about and then design gameplay around them. So, I see more games building story arcs and characters that you care about, and then making them fun. Where is that all going to go? Nobody really knows.

Matt: Nobody really knows, but we’ll all be interested to see — and hear.

Greg Edmonson: Exactly, exactly! That’s why I’m so thrilled to be a part of it.

Matt: Music from Uncharted was recently performed by the London Philharmonic Orchestra for a special concert and album release. How does it feel to be involved in this production? What does it show about Uncharted’s place in the history of games and their music?

Greg Edmonson: I think it’s thrilling! All I want to do is write music that touches people’s lives and makes it fun for them. So, how lucky am I to work on a project like Uncharted that reaches so many people. I did some of Video Games Live concerts, are you familiar with those?

Matt: Yes, absolutely! Tommy Tallarico-

Greg Edmonson: Yeah! I must say, they have the best fans in the world. I mean, sci-fi fans and gamers? You can’t do better than that! And I understand part of the reason why: when you score a film, people spend maybe two hours watching a film. But if you score a game, even if the music is deconstructed (and it will be) because you can never write enough music to fill an entire game, people spend time, a lot of time with that music and it has an impact on them. So to be a part of that? How lucky am I? The fans are just great!

When I go to Video Games Live and conduct a piece or two, the fans respond to it. It’s amazing when it’s over and people clap and you realize how much meaning it has to them. All hats off to Tommy for creating such a thing because he knew that as gaming became such an integral part of people’s lives that these concerts would have meaning to them. I’m just thankful to be a part of it.

Matt: Jumping back to Drake’s Deception, the soundtrack has been rewarded with a double disc release by La-La Land Records. Can you elaborate on what we should expect from the album? What could you offer across two discs that couldn’t be condensed into a single disc like previous Uncharted soundtracks?

Greg Edmonson: It has a whole hour of music that the iTunes version doesn’t. For instance, there are places in the desert where Nathan Drake is kind of under the influence. I’m thinking of the right way to say this so there aren’t any spoilers, but let’s just say he’s under the influence (laughs). Jonathan Mayer who works at Sony (and has worked with Azam Ali before) did some music that was going to be deconstructed and was really kinda trippy. I didn’t write that, but it’s a part of the game, so they included a lot of additional pieces of music in order to reconstruct the “Uncharted” experience. But it’s not just all about me as a composer; for the gamer it’s about the Uncharted experience and a lot of that is on the CD.

Matt: You have also worked on several movies, including the recently released Montana Amazon. Out of all the movie productions you have scored, which would you say are most memorable?

Greg Edmonson: I almost can’t think that way. Everything has value for its own reason. I’ve done some really good projects and I’ve done some… less good… projects, but every single one that I do, if I can walk away saying ‘I learned something’ then I’m really thrilled because that is how you grow. I’ve yet to do a project, even a bad one, where I don’t learn something. There are always some tricks and some things you learn that you wouldn’t have learned had you not done the project so I can’t really quantify favourites.

But if you asked what my favourite latest and greatest project is? Well, Uncharted 3! (laughs) I broke personal ground with that project that I don’t think that I would have broken if I had not done that score. I learned more about using the orchestra in exactly the way that I intended than I ever have before. Again, if you learn anything from the project then it was a good project.

Matt: Many thanks for your time today, Greg Edmonson. Is there anything you’d like to say to your fans of Uncharted 3 or your music in general?

Greg Edmonson: I really don’t know what else I can say but thank you. I have been so honoured and so humbled, so thrilled that anyone cares, that I can’t think of enough good things to say to the people who take the time to listen to the music and allow it to have meaning to them. I truly am humbled past the point that words cannot serve me because there really aren’t enough good things to say.

I am so lucky that I do this for a living, and I know how lucky I am. There are guys in my business who want to be big, or famous or rich. Those never have been desires of mine. I like being successful and I like the concept of money (laughs), but those aren’t ultimately the things that matter — they’re really not. I want what I do to touch people in some small way, and how lucky I have been. I am thrilled to be a part of the games industry, and I can’t do better than working with Naughty Dog and Sony. How lucky is that?

Matt: Well, we’re all lucky to have you scoring such a great franchise as Uncharted and to be in the gaming music community in general so thank you very much for everything.

Greg Edmonson: It’s kind of you to say so, but the pleasure is all mine!

Posted on November 15, 2011 by Matt Diener. Last modified on February 27, 2014.