The 10 best themes of Marvel vs Capcom

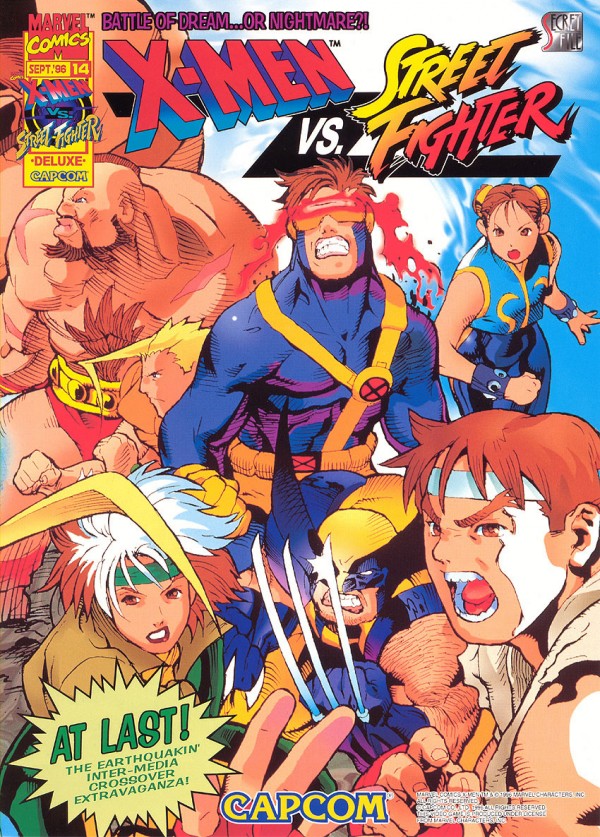

The symbiosis of Marvel to Capcom in the mid 1990’s must have been uncomfortable for both parties —at least while the deal’s ink was in its infancy. Marvel, as a juggernaut brand, was simply not doing as well as it had been, and alarmingly so. Seemingly jaundiced from an exodus of talent, a collection of mergers, distribution revisions and general sales slumps, Marvel was perhaps intrigued, desperate, or both when it saw the initial draft Capcom had slid across that boardroom table. Capcom, relishing the power afforded to it by a decade of commercial and creative success, felt emboldened enough to offer up not only a single measure, but a stable of software utilizing the most bankable of Marvel and Capcom’s wheelhouses of available glitz. The order for multiple releases (at least on Capcom’s part) could be seen as an act of faith—a gesture of goodwill. More likely, however, Capcom saw it as a litmus test to gauge the viability of Marvel’s seemingly waning muscle to bring home a rise in Capcom’s own shares over the long-term. In the same way, Marvel was unlikely sold by the cursory tour of Capcom’s coruscating warehouses, and agreed to terms with equal measures of ambivalence and skepticism. The final details and written signatures were as much a truce as an amicable contract of workmanship.

Capcom’s schedule of delivery included Punisher in 1993, followed by X-Men: Children of The Atom in 1994, and Marvel Super Heroes followed shortly thereafter in 1995. The partnership truly began to flourish with 1996’s X-Men vs. Street Fighter, and the bolstered arcade earnings was a monetary success that was not lost on either corporation’s conclave of CEOs – disconnected, adrift or otherwise. The sequel is fast tracked and delivered as 1997’s Marvel Super Heroes vs. Street Fighter. With the arrival of Marvel vs. Capcom in 1998, a once sordid alliance became a declaration of matrimony. With the arduous courtship now behind them, so came a sumptuous largesse—a meticulous sonnet in faultless form: Marvel vs. Capcom 2. The rest of the story is very much written and likely, you’ve heard it. However, history, (or my version of history), is not the purpose of this article. Today, we will be celebrating the top 10 greatest pieces of music found within Marvel and Capcom’s versus series. To be clear, this list will cover only those titles where both companies converge. Therefore, the Punisher, X-Men: Children of the Atom, and Marvel Super Heroes will remain absent from these proceedings as will the gorgeous SNK and Tatsunoko versus pantheon. Those are for another day…

#10. Ultimate Marvel vs. Capcom 3: “Theme of Phoenix Wright”

Composer: Hideyuki Fukasawa

When Capcom began the heavy labor for what would finally emerge as Street Fighter 4, composer Hideyuki Fukasawa was tapped early and often to contribute to the string line. The results so impressed Capcom that they made Fukasawa acting compositional deputy in charge of some of the company’s highest profile releases of the era: Street Fighter 4, Super Street Fighter 4, Super Street Fighter 4: Arcade Edition, Ultra Street Fighter 4, Marvel vs. Capcom 3, Ultimate Marvel vs. Capcom 3, and finally, Street Fighter X Tekken. In what must have felt very much like a nightmarish melange of fever dream and waking state, it’s probable to say that the bubbling cool of champagne at each game’s launch party was, in fact, the only respite Fukasawa indulged in from the years 2007 to 2012. As was the custom, Fukasawa would swallow the contents of the single glass whole, shake no hands, and taxi home—wholly dismissing the high-life waves of congratulatory posturing trailing in vapor behind him. Later (that same night), he would begin tracking new material—a newly appointed zero-hour was already fast approaching. It’s no sane way to live, but Capcom’s unspoken wishes were already a motion carried in Fukasawa’s mind. The highly agitated, invariably tousled meter of Phoenix Wright is something Fukasawa channels to peak ascendancy as he stammers out Wright’s garbled pentameter of lovesick jilt. “Theme of Phoenix Wright” also serves as a line of demarcation where perpetually stalled rejuvenation suddenly twirls, and bends to a second wind.

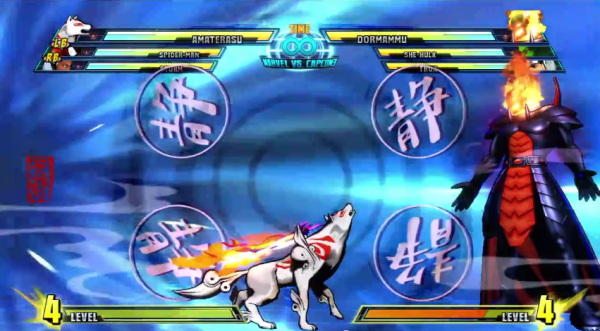

# 9.Ultimate Marvel Vs. Capcom 3: “Theme Of Amaterasu”

Composer: Hideyuki Fukasawa

The odds of the eventual arrival of Marvel vs. Capcom 2 were, at best, preposterously low. While the first Marvel vs. Capcom had done extraordinarily well, the idea of re-securing expired licenses and satisfying its parade of creative keymasters must have been an unparalleled logistical and fiscal nightmare. So, when Marvel vs. Capcom 2 finally disembarked from its fleet of high-sailing ships and was launched into the darkened steamy dens of arcade halls nationwide, one thing was glaringly apparent to fans: its score had been mercilessly overhauled. Despite Capcom’s most ardent intentions, Marvel vs. Capcom 2’s tracklist signifies a bizarrely aberrant compositional stalemate—a sequence of near stillborn miscalculations made in the name of expeditious demolition and nothing more. Capcom’s heedlessly bold experimentation seemed perhaps the only plausible avenue forward – a way to rid the series of its deeply embedded, age-old character themes. It was a proposition that ostensibly remained far too frightening for any previous key-holding composer to actively counter. Why bother to tinker with an already established, highly successful – albeit routinely tedious – pantomime?

However, the problem wasn’t the repetition of themes, but the lack of variation among them from release to release—Wolverine was Wolverine was Wolverine. It was the perspective that needed adjusting—the ability to view from the top, and the side as well as underneath. Hideyuki Fukasawa, now a fair distance into his lengthy Capcom residency, was no stranger to expertly tilting all photographs placed in front of him. His conscientious and fascinating variation provides Fate of Two Worlds and Ultimate Marvel vs. Capcom 3 with a much-needed roadside defibrillation—restoring what worked while offering a path beyond destinations already traveled. One of the most gorgeous of these non-incumbent entries, “Amaterasu’s Theme,” remains nonpareil almost a decade after its initial creation. The presentation of the more subtly colored, the more subdued and muted variations to be found within Amaterasu’s tufts of scruff seem to ply naturally with the much more alacritous universe of Marvel Vs. Capcom. Fukasawa’s crowning synthesis is one that maintains Okami’s highly palatial foreground without wholesale sacrifice of Marvel vs. Capcom’s opposing musical aims.

#8. X-Men Vs. Street Fighter: “Theme of Rogue”

Composers Yuki Iwai and Yuko Takehara

It’s difficult to say exactly what Yuki Iwai may have feared more: the idea of composing for a deluge of future Marvel vs games, or the actual labor itself. At least in the former, notions are nothing more than vapor – they have yet to exist, capable of vanishing from thought, disappearing from schedule books, a dream. On the other hand, a physical work order is hand-delivered, lengthy, detailed, and, most importantly, comes with a deadline. X-Men vs. Street Fighter was likely a spreadsheet that garnered pain from first blush and then in perpetuity as it was some shades larger than the previous releases. With an obscenely ballooned roster and the headache of re-arrangement ahead, Iwai quickly discerned that she desperately needed a partner to complete the new treatise – enter Yuko Takehara.

Despite the slog that may have ensued, X-Men Vs. Street Fighter is the LP that defines the thematic composite that Capcom would use going forward – it’s simply that good. Thankfully, it hasn’t aged much (if at all), and that is due to the raw strength of a number of particular arias. In fact, “Theme of Rogue” shares actual DNA with the character, Rogue, as any search conducted with the words “theme” and “Rogue” in it reliably produce this signature piece. No other similar composition claiming to best Iwai and Takehara’s A-side interpretation of the X-men heroine exist, and no attempts to recreate its swooping vertigo or surmount its instrumental movements tick by tick have been made in almost twenty years. No compliment goes higher than that of a piece of music remaining the unrivaled definition of its title character.

#7. X-Men Vs. Street Fighter: “Theme Of Sabretooth“

Compsers: Yuki Iwai and Yuko Takehara

Most composers working in the gaming industry in 1996 used pseudonyms. Few, if any, were fully credited – risk-taking was unlikely to be rewarded. Yuki Iwai and Yuko Takehara were effectively being paid to write music that evoked spit, knuckles and blood – goalposts had clearly been marked. Instead, in truly obstinate fashion, our composers chose to siphon their orchestral gas from a completely unanticipated source: Ragtime. While it’s certainly a far cry from the likes of Jelly Roll Morton and Sidney Bechet, it’s relatively clear they took some inspiration from the genre in pursuit of their profile of Sabretooth. Iwai and Takehara could have fashioned Sabretooth as a character without dimension – a half-wit, a goon who is, as expected, malevolent. Instead, the theme’s final arrangement is a clash of truths – a manipulative piece – that not only accentuates Sabretooth’s violent, invariably off-kilter disposition, but also sets out to magnify his artful glibness, his quick wit, and his ability to blend with scores of laymen. Sabretooth’s foil, as provided by Iwai and Takehara, is one that forcibly shutters the watchful eye of everyone involved: While you should be on your guard, Sabretooth’s campfire ease holds you mindlessly spellbound – between his punchlines, the deathblow.

#6. Marvel Super Heroes Vs. Street Fighter: “Theme Of Norimaro“

Composers: Yuki Iwai and Yuko Takehara

Theme of Norimaro may, in fact, be among the least played signature character themes on this list and least known among fans in general. I won’t go into it too much, but you can blame various contract legalese for Norimaro’s exclusion in every region (save Japan). It’s a shame, really, because the Norimaro theme mostly serves as a cumulative agent of preservation for the sound of the versus series up to that point. Before any notation was ever inked to stave paper, Iwai and Takehara must have felt that, in some way, the accompaniment would drastically be altered, or their alliance severed in whatever form the Marvel/ Capcom association took next. In an effort to encapsulate the preceding years of work, the theme of Norimaro was groomed as an exit, a definitive bow beyond the proscenium line: the final, celebratory gasps of a creative partnership. The song itself feels very much like a trotting out of greatest hits, an extensive highlight reel aimed to italicize familiar flourishes that bear repeating. While some of the recording cast members being lauded are clearly absent, Iwai and Takehara were meticulous enough to ensure that the final call would indeed be representative of all fingerprints smudged into the glass.

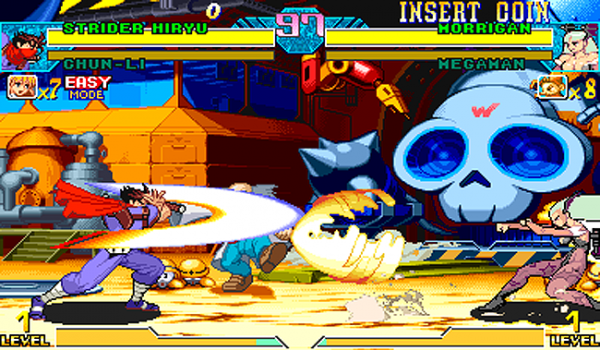

#5. Marvel Vs. Capcom: “Theme Of Strider”

Composers: Yuko Takehara and Masato Kouda

Strider Hiryu rarely does anything else aside from walking on. That’s it – a short shuffle onscreen, and off he goes. His time within the frame exists only to extend a legacy that he rarely has the chance to defend. That’s why, in his near 30 years of existence, he’s had only three bonafide games adorned with his moniker. Capcom immediately ordered the safeguarding of their newest acquisition – Strider’s participation in all forms of high contact sport was strictly forbidden. It’s for these reasons that his surprise inclusion in 1998’s Marvel Vs. Capcom was met with as many lavish parades as it was – it gave players a chance to Q and A, meet and greet, and watch the legend spar in ludicrously fixed exhibition matches – it’s what you do with a figure so beloved.

Composer Yuko Takehara, now newly partnered with fellow musician Masato Kouda, encountered few, if any, stumbling blocks when the order came from above to add further points of articulation to Strider’s slew of Vegas showroom residencies. Almost a decade earlier, as if blinded by his star, composer Junko Tamiya definitively created and perfected Strider’s gaudy flash with an entrance that included a lowering from the rafters as well as ample time in suspension above the audience. Capcom had already signed his backing band – everything was in place. And so our composers did the only logical thing a showman could do: they made it louder.

#4. Marvel Vs. Capcom: “Theme Of Captain America”

Composers: Yuko Takehara and Masato Kouda

Nobody in their right mind wants to face, nor haggle, with the abuse that comes with the responsibility of musical iconography. Fatigue and burn-out casualties are heightened, and begin to take shape almost from the onset of composition. If you worked within the Capcom ranks amidst this Marvel/Capcom merger, this was, in fact, a part of the daily order – analysis of minutiae, the re-sketching of character voice, the re-written lead-in. The time spent by in-house Capcom composers drew on – longer and longer and longer. Many times, the reward after months and months of commitment was the discovery that, somehow, their delineation was found to be in error. I suppose I don’t have to tell you what happened when they had to draw composition straws for Marvel Vs. Capcom…shuddering fear. Having already wiped away a crop’s worth of rotten produce, a file cabinet’s worth of venomous hate mail, and an amphitheaters worth of drunken hecklers, our composers Masato Kouda and Yuko Takehara, unfrazzled, closed their eyes and stuffed their hands into the rigged assortment of drinkware.. Surprise: It’s Captain America!

The skeleton of the original Captain America piece, written some years prior, was an able composition, but failed to evoke enough of the strength expected from a man draped in a flag and patterned long- johns. The original version lacked any sort of significant bellow, and was left to wallow in its own frailty – it was significantly improved upon by the repackaged version. This second make and model is a piece that effortlessly steered free of the original’s stagnated vanilla pragmatism. The remastered audio offered its biggest and, by far, most potent addition by way of a wholly revived opening monologue with force enough to jostle even the staunchest non-believer.

#3. Marvel Vs. Capcom: “Theme Of Morrigan”

Composers: Yuko Takehara and Masato Kouda

Mega Man’s theme was given a more pronounced and glossier sheen than that of his stable mate, Morrigan Aensland, either by natural design or letter instruction. In any case, Aensland’s scrupulously applied matte finish is one that mercifully breaks the harangue and monotony of chest-beating that Marvel Vs. Capcom overextends. Morrigan’s delivery isn’t usual. Nor is it prostrate, uninvolved or stiff idling. The play here is diaphanous and fluid, with the prescribed instrumentation an alluring mosaic of provocative synergy and dulcet seduction. The robust and elastic marrow of its jazz fusion origins makes for a much more supple base from which to draw, allowing for a surprising versatility that is scantily seen among the multitude of grooves to be found in this record proper.

#2. Marvel Vs. Capcom: “Theme Of War Machine”

Composers: Yuko Takehara and Masato Kouda

Most Marvel Vs. Capcom players have some form of penchant or compulsion to choose some combination of Spiderman, Wolverine or Gambit. It’s a conclusion not lost on Capcom brass. When watching the three contenders in their heat, running their paces, it’s obvious that liberal, judicious pressure was applied to every facet of tinkering with the sound of each of these musical monikers. The three themes, however, seem cut from overlapping templates where tone, structure and crescendo vary by only the slightest degrees of freedom. Each declaration is a near flawless facsimile of the last despite Spiderman playing a tad looser than Gambit, Gambit wailing slightly louder than Wolverine, and Wolverine snarling a bit more than both. They are, essentially, palindromes.

Theme of War Machine, however, eschews this tired vat of thick gristled pomp, and proceeds instead to mindlessly gyrate, scream and fist-fight for its divisive entirety. The theme itself resets and scrambles the preset by banging and whiplashing about a space with no mind to avoid placed obstacles. Feeling rawer than any of the three above mentioned banner titles, War Machine feels as tenacious as it does gratuitous – a live, unsettling throng of squalid rug burns. It’s the difference between stately play and dirty tricks.

#1. Marvel Vs. Capcom 2: “Take You For A Ride”

Composers: Tetsuya Shibata and Mitsuhiko Takano

Fumbling about the innards of Marvel Vs. Capcom 2‘s score is likely a prospect that will differ sharply from listener to listener. Although lambasted for its multitude of directionless marimba, its hustling, unsteady, trill Saxophone diatribes, and its corrosive tickling ivory chasm of wavering – yet unending – piano soloing, its etudes eek about their meager tightrope seemingly unperturbed by their own raucous cacophony. Half unmitigated Bronx cheer and an additional three-fourths of Jean Auel’s Clan Of The Cave Bear as vocalized by an imprisoned Carly Simon, Marvel Vs. Capcom 2, under the gleam of library microfiche, is a specimen that, at the very least, bubbles from underneath its celluloid – I’ve said this many times.

As a score, Marvel Vs Capcom 2‘s obdurate, grunted “pfft” disregards the steadied guidance of its versus peers, and becomes this record’s ostentatious stroke of divination. Marvel vs. Capcom 2 is an LP that trades its solid gold riffs for disposable cannon fodder without so much as a whiff of hesitation. Its garish inventory of cheap, inscripted, brightly set baubles offers no explanation for its set course, and instead, baffles with droves of hastily pronounced, oft erroneously strung together diacritic titillation. Almost two decades later, Marvel vs. Capcom 2’s song cycle remains unblemished by time, a chichi pearl of unequivocal, mislaid affection. It is perhaps the most poignantly crude, yet immensely popular off-label attraction that continues to entice those seeking a higher concentrate of thrills than that offered by the bizarre or the avant-garde.

Posted on September 23, 2017 by Eugene Lopez. Last modified on September 23, 2017.