Hiroyuki Kawada Interview: Namco Sounds in the 1980s

Hiroyuki Kawada is Namco’s longest-serving musical innovator. During his three decades at the company, he balanced work on classic properties (e.g. Galaga, Pac-Man, Xevious) with new properties (e.g. Ace Combat, Valkyrie, Time Crisis). For each title, he brought fresh styles and technical innovations. He was also responsible for bringing the series’ music to soundtracks, arranged albums, and even a theme park. He recently departed the company to work as a freelancer, but continues to collaborate with them on new projects, such as the recently released Pac-Man Championship Edition 2.

In this two-part interview, conducted with our Patreon supporter Stephen Burkett, Kawada gives an indepth insight into how he composed, implemented, and disseminated music for various Namco titles. In the first part of the interview, covering the years 1984 to 1989, he discusses his path to becoming a video game composer, the creative culture of Namco at the time, and how he led the Namco sound team. He goes into particular details about the various musical and technical innovations that brought his soundtracks to titles such as Winning Run, Galaga ’88, and Valkyrie no Densetsu to life.

Interview Credits

Interview Subject: Hiroyuki Kawada

Interviewer: Stephen Burkett, Chris Greening

Editor: Chris Greening

Translation & Localisation: Ben Schweitzer

Coordination: Don Kotowski, Go Shiina

Interview Content

Stephen: Hiroyuki Kawada, thank you so much for doing this interview and giving the West the opportunity to hear about your works. First of all, could you tell us about your musical background, education, and influences?

Hiroyuki Kawada: I studied classical piano from when I was 4. When I reached the fourth grade, I developed a fascination with the methods used in the pop and rock music that I heard in my everyday life, and I started to study the basics of contemporary music theory by attending music classes intended for adults.

When I reached middle school, my interest in rock and pop music won out over my interest in classical piano. My basic stance is that when it comes to what you love, you should begin by digging into it as far as you can without learning from others, and only then study the things you still don’t understand with specialists. That way you’ll know the joy of unravelling the mystery and progressing to the next stage. It’s the same with video games. Even art, which I loved, is based on acquiring the basics of drawing. With music, I didn’t get the urge to drop everything and study it at university. I subsequently went into unravelling the methods of jazz, and while I was going to college, I studied jazz piano and the Berklee method.

Around high school, I quickly went about acquiring all kinds of tools, including a synthesizer, an effector, a sequencer, and a multi-track recorder, and I took on the challenges of programming timbres and recording in earnest. My knowledge of the equipment and my experience with programming timbres would turn out to be useful in my job later on. I would continue to buy and collect the occasional instrument if I found something I liked, so today I’ve amassed a considerable collection of them, which is a bit of a problem… (laughs)

Going into college, the range of music I enjoyed continued to expand, and as a keyboardist I participated in a variety of bands in diverse genres including hard rock, progressive rock, cross-over, funk, pop, and world music. I think the fact that I was able to perform on the keyboard in so many styles and study the ensemble of various bands would provide a rich source of ideas and open up a wealth of genres for me as I composed later on.

As I enjoy such a wide range of genres, I’ve been influenced by countless artists, producers, engineers, etc., and there’s no way that I could list all of them. I would like to say that perhaps unexpectedly, I generally wasn’t influenced by video game sound much at all. When I got my start in video game sound creation, it was still the dawn of the field, after all.

Stephen: What then led you to becoming a video game sound creator?

Hiroyuki Kawada: To me at the time, putting off graduating from college, I didn’t think that the music I had been into as a hobby would ever translate into a job. I did have a faint understanding of the fact that my vocation was to be a “creator,” though, so I turned towards the video game industry, which had already interested me at that time and which was then experiencing a period of considerable growth. And the company that overwhelmingly stood out from the rest in terms of originality was Namco.

In 1984, when I graduated from college, I entered Namco as a video game designer, just as I had hoped, and I was taken into the development and planning department led by Toru Iwatani (the developer of Pac-Man). At first, I spent time studying video games from Japan and elsewhere, helping out with design work as an assistant, and testing video games. Being able to look over the specifications booklets for all of the video games I had ever played was pure bliss.

The turning point came afterwards, when I created the soundtracks for the promotional videos for Dragon Buster and Pac-Land. Based on the ability I had shown at that time, I was able to start work as a sound designer in 1986. Namco had just started expanding into developing games for the Famicom (NES), and they had many production lines all running at once, so they probably had an extreme shortage in terms of sound development staff.

Chris: I’m a little surprised that you were a designer first, a composer later…

Hiroyuki Kawada: A bit beside the point, but permit me a little digression outside of music.

When I was in elementary school, I loved to draw pictures, read books, and play soccer. I had started to play classical piano at age 4, but it wasn’t as if I had any particular passion for it. I loved to draw far more, and even as a child I would enter sketch contests and win prizes. I won a competition which resulted in my work being employed in mosaic wall art in a public facility. Even in high school, my major was in art, not music.

Here’s another interesting anecdote: when I was in elementary school in 1968, I won a competition which led to my being invited by the Lego company to provide a work for the opening of Lego Land Billund/Denmark. I’m one of the first Lego builders in Japan (laughs). I had loved block toys from when I was young, and I think that may have left its mark in my creative work by developing a sense of logic and design and by fostering a mentality of turning my ideas into finished works. It’s very little-known, but as a child I appeared in a Japanese commercial for Lego.

Chris: You were clearly passionate about building things all-round. Looking back at your first game soundtracks, what were the technical challenges associated with creating sounds for Star Luster and Star Wars back then? What are your memories of these projects?

Hiroyuki Kawada: The first project I worked on as a sound designer was Namco’s original Famicom game Star Luster.

From the sound side of things, I worked on the planning and production, and I created all of the music and sound effects. As you know, the Famicom was limited to only three channels and a noise channel, but I was fascinated by the unexpected power of a triangle wave in the bass region, and I found that its unique sound, different from short-cycle noise or analog, left quite an impression. My sound design for the game makes use of the particular quality of that sound to the fullest.

Whenever an idea for a piece or a sound effect came to me I would enter it into my HP64000 editor and check it in my sound test program. I would then revise it slightly and check it again. I would immerse myself in trying to optimize the idea that I had in my mind for Famicom sound playback and realizing it in an effective manner. It would take a good deal of trial and error and mastery of the particular parameters in order to get the sound in my mind just as I imagined it, but I was determined not to compromise.

In regards to sound production, I wanted to do as much as I could to immerse the player in the game’s situation, piloting the Gaia in the vastness of space, embarking on a difficult mission…so I took the bold step of making sound effects and environmental sounds the main focus and using the music only at the most important parts. That’s why I didn’t take the route of having light, happy music play as you shot down enemy spacecraft. For the environmental sounds in space (even though in space it’s always been completely silent…), I wanted to provide a particular ambience built on the warp sounds, and I think that aspect has probably stuck with many of the people who played the game.

By the time of Star Wars, I had also come to work in the position of sound director. I didn’t want to go for the same kind of heavy sound found in the movie soundtracks, so I emphasized the fun and the feeling of the action/shooting gameplay, with the Star Wars theme playing happily in the background music, giving the game a very different feel from Star Luster. Speaking of which, I’ve heard people say that the first person shooting stage where you’re travelling out in space bears a close resemblance to Star Luster, which I think is explained by the fact that both games shared a single planner.

Stephen: Released back in 1987, Yokai Dochuki is regarded as another of your defining works in Japan, but has received little exposure in the West. Could you tell us more about its traditional Japanese soundtrack?

Hiroyuki Kawada: Yokai Dochuki is set in something like the afterlife, so when your character dies within the game, the game over will be a kind of rebirth and reincarnation, which makes for a very unique kind of game. Because of that, I felt that even though I would be writing the music, it would require a tricky kind of direction. In the kind of world filled to the brim with fairies and evil spirits of all kinds, you would think that the music should have a dissonant and uneasy sound characterized by dark melodies, but I came up with the idea of doing the exact opposite and going with a techno-pop score featuring action game-like rhythms. The melodies are in a kind of Martin Denny-like style. which can be heard as sounding Japanese, and the tone is overwhelmingly bright throughout.

If you look very closely at the fairies that appear, all of them are either charming or humorous. We aimed at a kind of mismatch, but within the world of the actual game you never get the sense that anything is out of place, so it creates its own strange sense of what fits.

This extended to the sound effects as well, where I applied a comical approach over a serious one (I created all of the sound effects myself as well), and together with the background music, I think I was able to contribute to the enjoyment that players get from the game. The voices of Tarosuke and the demon (AD-PCM), by the way, were created by processing the voice of the planner, M, himself.

Chris: How did you implement this project?

Hiroyuki Kawada: Yokai Dochuki was the first game where I made use of FM synth (YM2151), but fortunately, I was already familiar with it since my days as a student, so that wasn’t really a hurdle for me.

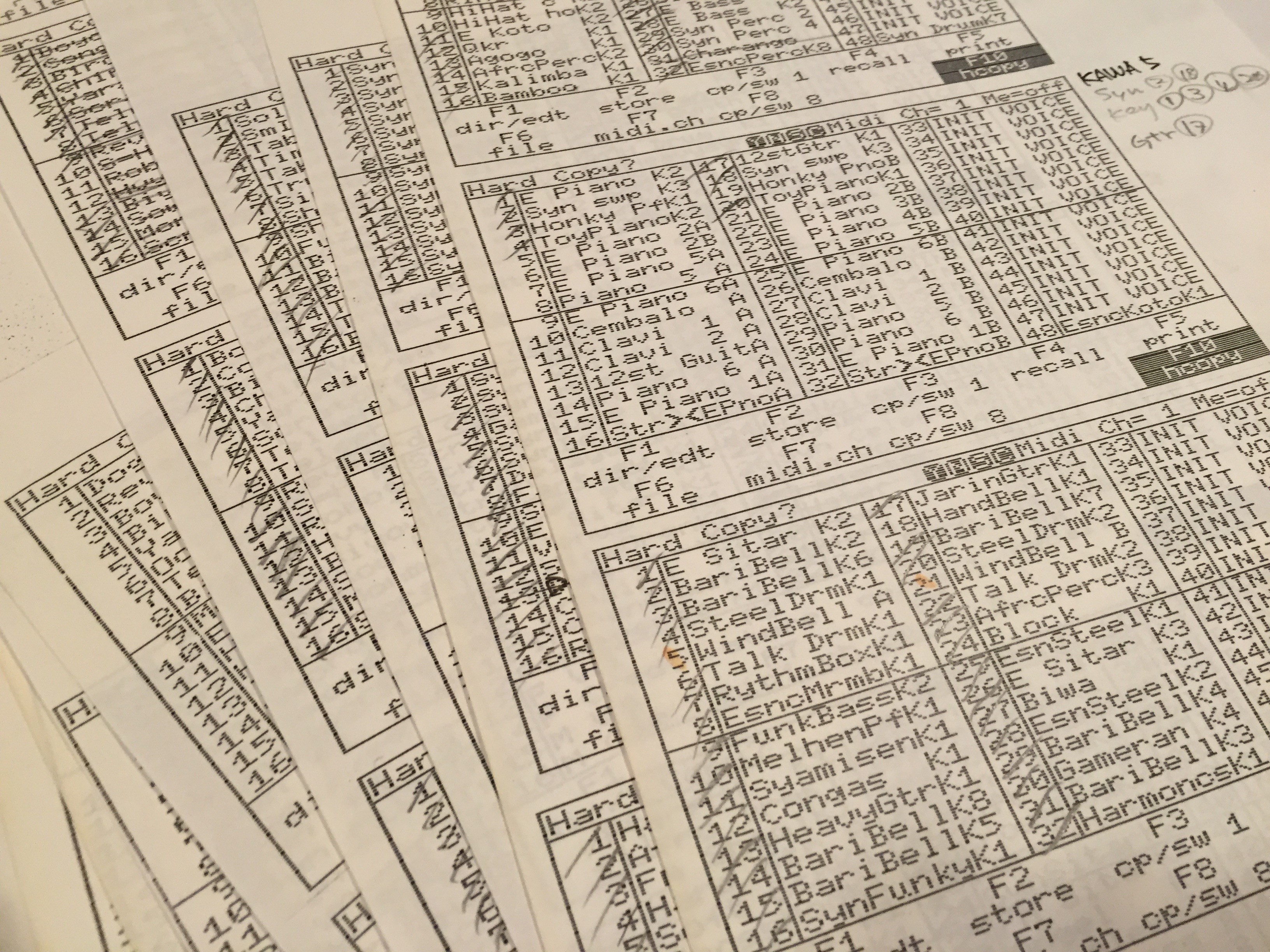

The difference from the wave table sound generator I had used to that point would be clearly appealing to players, and I worked hard to make the FM synth sound one of the standout points of the game. I remember how I created a library of over 1,000 unique timbres using the YM2151 timbre editing tool (FM Voicing Program YRM-12) on Yamaha’s MSX computer (CX series). I aimed to make sounds that were as colorful as possible.

One of the YM2151’s eight polyphonic voices had to be reserved for the credit sound, so the background music would be divided up over the remaining seven voices. In order to achieve a thicker sound with a small number of voices, I used algorithm 5, which allows for two operators, for the backing harmony in the music, so that two voices could be used to generate four voices. In other words, this made for a total of nine (5+2+2) voices out of the seven I could use. It was enough work to make anyone break down in tears (laughs).

Chris: On the arcade front, you’re also remembered for the music of Winning Run…

Hiroyuki Kawada: Right after I entered the company, I was informed that Namco had started development on some of the first 3D games in the industry. One was the driving game project that later became known as Winning Run, and the other was a seemingly little-discussed project, a subsequently cancelled space flight title connected to what would eventually become Star Blade. Both were top secret projects, so development went forward with only a few people even inside the company in the know. In actuality, despite the top secret nature of the project, the development of Winning Run went on in the room adjacent to the company’s reception area, where numerous visitors would come in and out!

For the sound, I wanted to match the 3D graphics, revolutionary for an arcade game at the time, with something that stood out from other video games. The music would have to take a direction that wasn’t merely game-like, something that incorporated near future elements. This was my chance to make use of all of the musical experience I had accumulated, from funk to rock to crossover to techno. This applied to the sound effects as well, where I used a vocoder to “sing” the coin sounds, etc. in what must have been a very novel effect for the time.

A little while after the release of the game, there was a Winning Run machine set up in an arcade that faced a street I was passing through near Shinjuku Station. There, I saw three young boys who caught sight of a 3D driving game the likes of which they had never seen before, and they were interested in trying it out. They inserted a coin, and were taken aback by a coin sound unlike any they had ever heard, all of them shouting out “Cool!” It doesn’t need to be said how much I felt like doing a victory dance in my mind right at that moment.

Stephen: Whereas Winning Run featured funk music, Valkyrie no Densetsu was an orchestral score. Could you tell us about how you developed the unique sound for this soundtrack?

Hiroyuki Kawada: The development schedules of Valkyrie no Densetsu and Winning Run overlapped, so I had no choice but to work on the sound for both of them simultaneously. One was a car racing game where players competed in terms of time and driving technique, while the other was an action role-playing game, structured by story, where players had to solve puzzles and fight with swords and magic, so I was working on two completely different kinds of projects at the same time.

Even so, the effect of combining both of those extremes proved unexpectedly stimulating to my creativity. In the middle of writing the music for Winning Run, which emphasized beats, I was coming up with all of these melodious ideas for Valkyrie no Densetsu, and the same was true in the other direction. Naturally it was quite a strain in terms of the workload, but I remember how working over all of the ideas for composing would have a refreshing effect and allow me to continue creating.

Incidentally, I thought up the main theme of Valkyrie no Densetsu in the middle of the kickoff meeting for the project, and I quickly scribbled it out in the corner of one of the various documents that had been handed out to me. Often, an idea that comes immediately will be off the mark, but I feel there is a certain fascination and power in ideas that were produced without a long thought process. In the years that followed, I would continue to get ideas for music and sound in the middle of the first meeting or the moment I received a new project over the telephone. Of course, that method doesn’t always work out the way you might hope (laughs).

Chris: What were the technical challenges of bringing your music to life on these projects?

Hiroyuki Kawada: Valkyrie no Densetsu used a System II board, while Winning Run used a System 21 board. Both of these boards had a Namco custom made “C140” PCM chip loaded onto a Yamaha YM2151, which provided an extremely high level of performance in terms of sound specs. In order to get the sounds I imagined to come out of the C140, however, I had to study sampling technology, which took a great deal of patience to master. People who experimented with early sampling machines will probably know about this, but if you simply tried to sample sounds as-is using the C140, it would inevitably produce a feeble sound when it came out of the chip. I spent a great deal of time studying how to get the sound that I was looking for and how, at the same time, to keep the amount of data within reasonable limits.

I had to use all kinds of techniques to improve the sound and expression: I would use EQ cuts to process out the frequency bands that I wouldn’t need before sampling, or detune waveforms to prevent them from sounding too boring and intentionally create short cycle vibrations (this also made for efficient loops), and use compression and other methods so that the volume envelope was pretty much entirely flat before loading it onto the on-board sound driver and recreating a more musical sound for the envelope.

In regards to the envelope, I needed to recreate the richer sound that recovered the inflections of the wave forms that had been discarded to create more efficient sampling, and I had to plan out envelope functions for the volume and pitch that would allow more nuanced control than the normal ADSR, and I added these onto the sound driver (all thanks to my sound programmer who worked on the coding!). At that time, whenever I worked on a title and wanted to do something new, the functionality of the sound driver would be upgraded so that I could accomplish what I had in mind.

Chris: Galaga ‘88 was a major step forward sound-wise compared to Galaga. Could you explain how you brought richer melodies, varied styles, and high-quality samples to this score? How did you interact with the rest of the development team to help bring about these goals?

Hiroyuki Kawada: Galaga ’88 was an extremely entertaining shooting game. That’s why in producing the background music and sound effects, I wanted to aim in the direction of entertainment rather than stoicism.

For the challenge stage, That’s Galactic Dancin’, people can enjoy a variety of music genres, which wasn’t based on any request from the planners; it wasn’t that the “dance” of the galaga was finalized and I wrote the music to that. I wrote the music first, and the planners choreographed the “dance” to what I had composed.

My tastes in music are truly eclectic, and I’ve always been interested in a variety of genres and performed across genre lines. That experience has allowed me to employ the vocabulary of all kinds of styles. I’ll never forget how the game’s planner drew on the movements of actual marching bands, and created “choreography” to match the march, tango, and swing jazz pieces I had composed.

Galaga ’88 used Namco’s System I motherboard, which had a Yamaha YM2151 chip, Namco’s custom wave table sound generator, “c30,” and a sound chip with 3 kinds of DAC (this shows you how much of an emphasis Namco placed on sound at the time). I loved bringing together the richness of the timbres in FM synthesis, the wave table synthesis that played a crucial role in the Namco sound, and the PCM synthesis that was indispensable for those low resolution real sound effects. When they were all combined and their distinctive colors were used to the fullest, it was possible to create a wealth of musical variety to complement the classic traditional sounds of the Galaga series.

The picture shows albums from the Video Game Graffiti and Game Sound Express series, released by Victor Entertainment, featuring Hiroyuki Kawada’s scores for Star Luster (top), Valkyrie no Densetsu (middle), and Solvalou (right).

Stephen: Sound team members from other companies in Japan have stated that work conditions were extremely challenging back in the 1980s. What was the company culture like at Namco during this era and how were you treated?

Hiroyuki Kawada: At the time, Namco sound designers were in charge of every aspect of the sound in a game from planning (how sound was used, melodies, the direction of all sound effects, etc.), to production. Working exclusively as sound directors, we would be able to provide a highly original experience for each title, employing all of the creative ideas we wanted to try out, which I think led to the very positive fan reception.

Looking back on the work environment of that era, I can’t leave out the fact that the top talent at Namco, including members of the development team (planners, programmers, graphic designers) possessed a very high level of understanding of sound development and a cooperative spirit towards it. I believe that the old Namco sound was a result of that particular corporate culture and the teamwork of the entire development staff.

That was why, in my position as head of the sound department, I hope I was able to make some contribution to the development of video game music by bringing in outstanding talent, assigning personnel to each title, expanding game sound specs, adjusting the development environment, and working with outside record companies.

The second part of this interview, set for release next week, covers the years 1990 to present. Kawada discusses how he brought game music to CD through various soundtrack releases, arranged albums, and independent productions. He also discusses how he brought diverse and contemporary sounds to various new franchises, before reflecting on his latest project Pac-Man Championship Edition 2 and his future plans.

Posted on September 18, 2016 by Chris Greening. Last modified on September 18, 2016.