Final Fantasy X Piano Concerto Listener’s Guide

Overview

In this three-part series, I am taking a deeper look into the major works of Spielemusikkonzerte’s Final Symphony album, featuring new large orchestral arrangements of music from Final Fantasy VI, VII, and X, performed by the London Symphony Orchestra. In the previous article, I detailed Roger Wanamo’s Final Fantasy VI symphonic poem, breaking down the narrative that he presents through the placement of themes, and detailing the way he signifies different characters and events over the course of the work. In this article, I will delve deeper into Masashi Hamauzu’s piano concerto arrangement of themes from Final Fantasy X (composed by himself and Nobuo Uematsu), with the orchestration provided by Wanamo.

While Wanamo’s symphonic poem was very accessible, clearly representing the game and story that it drew from, Hamauzu’s piano concerto is the polar opposite, purposely not having clear ties to the narrative and characters of its game. Although he chooses a handful of recognizable themes, Hamauzu doesn’t shy away from giving them far-removed variations to craft a new experience. This is in part due to influence from Hamauzu’s own compositions which tend to be impressionistic and very different from Uematsu’s more typically lyrical output. He has noted that this concerto partially realizes his vision of the Final Fantasy series as a “continuum”, and allows him to express things that he could not while working on the original Final Fantasy X score.

So for the concerto, it may be said that Hamauzu is making a new painting out of the colours and textures of the Final Fantasy X score. As a result many listeners have noted that the concerto is much less familiar and at times even unrecognizable as a work based on Final Fantasy X, but it is precisely for reason that I find the concerto the most engaging of the three major works of Final Symphony. This article is less of a “listener’s guide” and more of my own interpretation of the piece, but I hope this allows other listeners to form and enhance their own interpretations of this wonderful work.

If you haven’t yet picked up the album, feel free to follow along with the album on streaming services such as Spotify, as I have included timestamps throughout this essay.

The Piano Concerto

For his part, Masashi Hamauzu’s arranges various themes from the score of Final Fantasy X into a piano concerto. In this type of composition, the piano shines from among the orchestra, often having solo passages distinct from the accompanying orchestra as well as many segments that are like dialogues between the two elements. Piano concertos have generally (but with many exceptions over the years) employed a three-movement structure: an initial movement in a sonata-allegro form, a slow movement typically with a free form, and a final movement often in rondo form.

Hamauzu’s piano concerto does follow the three-movement structures, though he avoids the typical sonata-slow-rondo forms. The first movement instead features a set of variations on a single theme, altering the mood in each while keeping the general figure of the theme. The second movement is roughly in ternary ABA’ form, while the third movement joins together two originally separate pieces. Although each movement has a namesake music theme, the themes are not restricted to their respective movement and make small appearances in the other movements.

The Story

Final Fantasy X features many characters and story elements, but Hamauzu’s arrangement chooses to focus on thematic elements rather than the narrative of the game. The game follows a group of travellers on a pilgrimage in hope of defeating the entity that terrorizes their world, which is a monstrous being called “Sin”. The game tackles many conflicts and issues aside from the central conflict with Sin, such as racism, false hope, sacrifice. Some of the recurring elements include dreams, prayer, and home.

The Themes

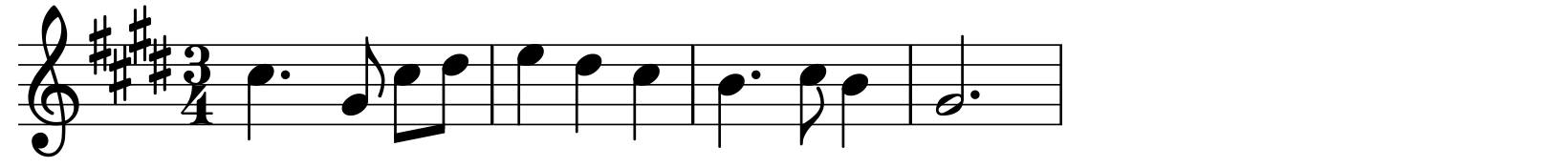

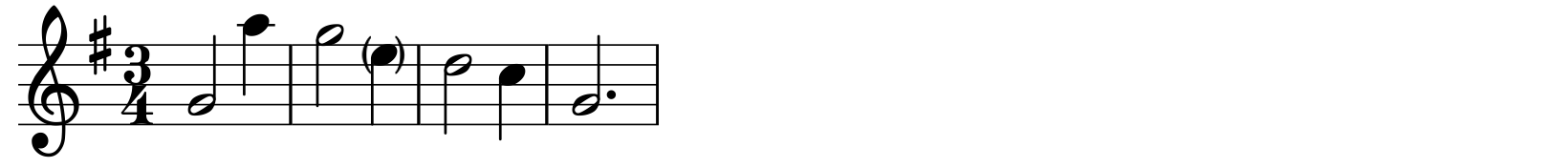

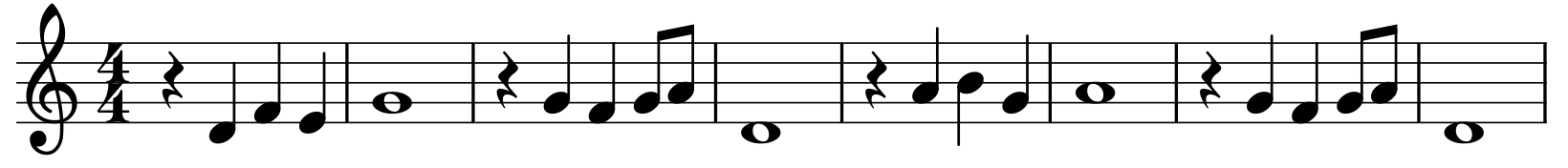

The score for Final Fantasy X includes over four hours of content, assigning themes and leitmotifs to the many different characters, locations, and events throughout the game. The score was composed by Nobuo Uematsu, Masashi Hamauzu, and Junya Nakano, though only Uematsu’s and Hamauzu’s themes make it into this concerto. The following are the themes that are included within the piano concerto, with information about the context of the pieces within the games. The alternate names listed are translations of the Japanese names. This article will refer to the pieces by their proper English names. I’ve provided samples of the recurring leitmotifs to help with identification.

“Zanarkand” (aka “At Zanarkand”) by Uematsu is originally a melancholic piano solo, and takes its name from the former metropolis Zanarkand, which lies in ruins in the game. The city is the northernmost location on the continent and the final destination of the pilgrimage that the characters follow. The track only plays during the opening credits, as well as during the first scene that occurs when the characters enter the city. The track also goes by the name “To Zanarkand”.

“Besaid” (aka “Besaid Island”) by Hamauzu is originally a bright track with synths that invoke the feeling of water. It plays on the Besaid Island, the southernmost location on the continent and the starting point of the pilgrimage. The island is also the home of many of the main characters.

“Hymn of the Fayth” (aka “Song of Prayer”) by Uematsu has several iterations in the original score, either with a solo voice or in a choral arrangement. Many of them play within the inner chambers of the temples, while other versions play at certain key events. “The Sending” is a version of “Hymn of the Fayth” that plays during a ceremony for guiding souls of the dead to the afterlife. It accompanies a unison choir rendition of the hymn with ceremonial instruments and arrangement.

From the second movement, “Thunder Plains” by Hamauzu is an upbeat, metronomic piece that plays in the Thunder Plains. Although the piece is light and bouncy, the track is in stark contrast to the actual Thunder Plains, which are gloomy with a constant downpour of rain and lightning. “Yuna’s Decision” by Uematsu is a laid back track that plays in the Calm Lands, a wide and vast grassy area with a gorge known as “the Scar”. In years past, Sin was fought in this location.

From the third movement, “Assault” plays during the attack on Bevelle, and is a quicker version of the airship theme. “Final Battle” (aka “Decisive Battle”, “Kessen”) plays during the final confrontation of the game, and incorporates variations of some of the other themes from the Final Fantasy X score.

The Work

The first movement “Zanarkand” features two songs, “Zanarkand” and “Besaid”, with several variations on the former theme. Throughout the course of the movement “Zanarkand” is never played straight from start to finish, possibly due to the abundance of existing faithful arrangements. In this movement more than in the rest, Hamauzu puts this idea of a “continuum” to use, allowing the “Zanarkand” motif to journey through several landscapes completely different from its native ruined city. In the course of the movement we hear the theme represented in all sorts of flowing images with feelings of tranquility, growth, wonder, excitement, and danger. Almost every melodic phrase we hear in this first movement is some variation on at least a fragment of the “Zanarkand” motif (eg. 1:38), though Hamauzu also includes flashes of “Hymn of the Fayth” (4:04) and “Final Battle” (4:38). The Zanarkand motif finally shows up in its proper form (5:46) in the strings, though the piano doesn’t catch on until the climax of the melody.

The movement, however, doesn’t finish with the end of pilgrimage in Zanarkand. Rather the movement returns and finishes home in “Besaid”, starting with watery trills (6:33) that eventually lead to the full theme (6:59). The “Zanarkand” motif continues to makes brief appearances, recanting the journey to those who had stayed behind. The combination of themes is not only found here, but also in fact at the beginning of the journey when “Besaid” provides the trickling texture and rhythm early on (1:31), although its melody was not yet present.

There’s a lot that could be said about the significance of all of this. “Zanarkand” is a track that represents the end of the pilgrimage, ruin, stasis, loss, and also dreams. “Besaid” on the other hand represents the beginning of the pilgrimage, home, change, hope, and rebirth, all in contrast to “Zanarkand”. Even the areas they represent are polar opposites within the original game, being the northernmost and southernmost points of the continent respectively. So in a loose narrative sense it can be a vague representation of the pilgrimage and the return home, but the unity of the songs in the movement suggest a close intertwining of the concepts that these themes represent: hope through suffering, familiarity in the midst of change, the cycles of life, the memories and dreams that we will never forget…

The second movement “Inori” (Japanese for “prayer”) begins and ends with iterations of “Hymn of the Fayth” separated by “Thunder Plains”. The “Hymn of the Fayth” begins simply with parallel fifths, an ode to Gregorian organum and the chant-like nature of the original piece. Even as the arrangement becomes more complex, Hamauzu keeps the interval of a fifth in many of the chords. Throughout the movement Hamauzu fills in the periods of quiet between the four-note figures, and in this first section he often modulates the key before the full melody can even be finished. Just as the full melody is about be heard plainly (2:06), Hamauzu cuts it off and moves on.

In the middle segment, Hamauzu turns his attention to the bouncy and perky “Thunder Plains” (2:36). It is very different from the solemn “Hymn of the Fayth”, but this is what ternary form pieces typically call for. Rather than keeping the arrangement steady and metronomic as in the original, Hamauzu livens things up, allowing for more flow and development than the original. Things even get a bit dramatic and in the height of this, “Yuna’s Decision” peeks out in the eye of the storm for a short reprieve (3:48) before returning to the dizzying chaos of the “Thunder Plains” (4:10). In the end, the Plains are crossed, and Hamauzu retreats back into prayer.

When the “Hymn of the Fayth” returns (4:55) it begins with the same opening fifths, but some faint, offset percussion can be heard in the background. Gradually the strings and the percussion become more prominent, and the piece blossoms into a sublime rendition of the ceremonial track “The Sending”. Wanamo deserves a lot of credit for translating the exotic sounds and effects of the original to work with the orchestra in this arrangement. All of the elements flourish here, and the piece forces up the tension with the wails and cries of the dead, releasing the energy into the explosive final movement.

The third movement “Kessen” (Japanese for “decisive battle”) is a straight combination of Hamauzu’s “Assault” and “Final Battle” with a few added segments and ornaments. The tracks are very faithful to the originals, but that’s alright; the concert hall has been aching to hear live renditions of these masterful Hamauzu works. I’m fairly convinced that Hamauzu has an entirely unique sound when it comes to the prominent use of the piano in action-packed tracks, and it shines here. There is a deft mix of grand orchestral movements alongside virtuosic and chaotic piano work throughout. It seems typically unthinkable to have a piano at the centre of an bombastic action track when the orchestra is being unleashed, but in Hamauzu’s pieces the piano is taking a lead in the battle, never taking just a supporting role. Hamauzu even gives the piano a more prominent role than it had on the original version of “Assault”, and indeed the pianist gets almost no breaks on this stamina-testing movement.

With this Hamauzu launches a full-scale attack in “Assault”. The piano pumps up the orchestra in the bass, all the while issuing commands to the fellow instruments. It leads the way into battle, taking first strike with the melodies before the rest of the orchestra follows suit. Throughout the movement there are shifts of view from the gigantic battle with the whole orchestra to the more intimate moments between the piano and its immediate solo instrument companions. As the defending army falls and the orchestra narrows in to its target, the piano gives one last rousing speech with a reiteration of the “Hymn of Fayth” (1:47), and the time comes for “Final Battle” (2:06). The fight is frantic, and after brutal segments the strings shout “Zanarkand” (2:58) in a final rush of adrenaline. Soon, the last blow is dealt, and the piano confirms that the battle is over by finishing the “Zanarkand” melody (3:42). A shout of joy erupts from the orchestra, and the concerto is finished.

Summary

That’s it for our look at Hamauzu’s take on Final Fantasy X’s themes, though the conversation should definitely not end here! What I’ve presented is simply some of what I personally gathered from the concerto, and I’m sure that other listeners can draw many other interpretations as well. I also expect that Hamauzu has hidden plenty more tidbits in all of those less familiar transitions and figures. It’s these surprises along with the unique textures and arrangements helped by Roger Wanamo’s expert orchestrations that make this concerto so alluring, and I’m sure it will continue to entertain for a long time to come.

Side Notes

-The concerto has seen a number of changes since its premiere. At those first performances, the “Besaid” theme had a slightly different and longer introduction, which was taken out here in favour of the clear statement of the “Zanarkand” theme that comes just before “Besaid”.

-The recapitulation of “Hymn of the Fayth” was also different in these early concerts, focusing on the piano and strings dynamic. The transition to “The Sending” replaced this.

-I call the “Inori” movement roughly ternary form despite of the inclusion of “Yuna’s Decision”, which technically gives the movement ABCBA’ rather than ABA’, because the interjection is short and nearly negligible. But what is “Yuna’s Decision” doing in there? The Thunder Plains lie in the central of the continent in Final Fantasy X, and its theme is in the middle of the concerto as well. “Yuna’s Decision” is placed in the midst of it, and I wonder if it actually refers to her decision to marry Seymour made at the midpoint of the Plains, although the theme does not play at that time in the game. Perhaps things in this concerto are more narrative than I thought.

-There is a mysterious rising major second motif that occurs a few times throughout the piece. It first is played by the horn in “Zanarkand” (0:36), but from there it is imitated by the piano in the same movement (1:14) and again in “Inori” (1:39). I honestly have no clue what its purpose is, but I’ll let you know when I find out.

-Is anyone else convinced that “Final Battle” includes loose variations of “Battle Theme” and “Suteki Da Ne”? No? Should I stop looking for loose variations where they probably don’t exist? Ok.

If you haven’t seen them yet, check out the guide to Roger Wanamo’s Final Fantasy VI symphonic poem, as well as the guide to Jonne Valtonen’s Final Fantasy VII symphony in three movements! Also check out the official website to find out where you can purchase the album.

Posted on March 12, 2015 by Christopher Huynh. Last modified on August 24, 2023.

Great analysis Christopher, and I’m happy to finally see the appreciation and in-depth look at this stunning piece! I really think this concerto is one of the greatest artistic achievements by Spielemusikkonzerte so far, and I hope that Masashi Hamauzu will arrange more music for this series.

Also – interesting to see how you noticed the rising seconds as I find it so intriguing too! To know where it comes from, I think you have to look at the very end of the concerto; at 3:50 in the 3rd movement you can hear it concludes the last Zanarkand phrase and in fact some more phrases in the original Zanarkand theme end with this rising second. Like you said, it’s apparent in the introduction of the first movement, and later on it’s played as accompaniment by the strings during the Besaid section. Also, you can hear it in those ‘wailing’ clarinets during ‘The Sending’.

Then what happens in Assault is interesting too: After the first statement of the familiar material, at 0:32 he changes the original track and substitutes it with something that consists of….. again seconds! And then at 0:49 there is also a reference to ‘People of the Far North’, which is quite interesting too. Also, yes, I agree that there’s definitely a reference to Suteki Da Ne in the Final Battle, as well as in the first movement of the concerto. Adds to the overall structure of the piece I think. Oh, and I wonder who else thinks that the bass drum hit at the end of the piece is a nod to Ravel’s G major concerto, since this Concerto ends in the same key. 🙂

I definitely agree with you about Hamauzu and this piece, and I’d be totally on board for a FFXconcerto-2. I would love to hear his take (with Wanamo’s orchestration) on Wandering Flame. Just imagine.

I had noticed some of those things you mentioned in regards to the rising second interval as well, but the isolated instances are so particular that I hesitated to attribute those other instances to it. But that could very well be it.

I don’t know that the 0:32 section of “Kessen” is very different, I think it’s simply the piano taking on what was already in the original (~0:55 of the original, more pronounced in the remaster), but I definitely didn’t notice “People of the Far North”! I feel like I should have, and it’s definitely there…thanks for pointing that one out!

If there’s anything I’ve noticed in these (and the other long works from the Spielemusikkonzerte) it’s that Wanamo and Valtonen love to throw in references to other composers, so I certainly wouldn’t be surprised at the Ravel reference.